I used to be an idealist. I joined the Peace Corps, lived in a small village in Africa for two years and expected that I would work in international development and policy when I completed my service.

I used to be an idealist. I joined the Peace Corps, lived in a small village in Africa for two years and expected that I would work in international development and policy when I completed my service.

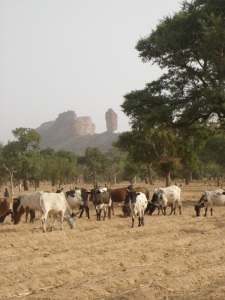

But I was incredibly disappointed by the ineffectiveness of aid programs I encountered in Mali. Generally speaking, none of the large development aid programs I observed had any real, sustained impact. (I define “sustained” as self-repeating: an investment that causes a positive feedback cycle of economic, cultural, environmental or social activity). I saw a lot of one-off construction projects and give-aways.

Governmental aid agencies and NGOs were eager to get work done, spend money and were not careful about corruption issues. I saw a lot of money misspent in my two years in Mali through laziness, corruption and incompetence.

In the end, I have a more basic problem with aid: Gifts, grants and giveaways make people less like to build things for themselves.

One of the examples I offer in this regard is from a village in western Mali. This small town had a market garden built for them by an international NGO, with several wells that had been constructed by another NGO. When a fellow volunteer started her service in this village, two of the three wells had collapsed and needed to be rebuilt.

My colleague asked why the village council didn’t get organize an effort to get the wells repaired, and her neighbors said that they were waiting for an NGO to come along and do it for them. The wells had been built by somebody else and the village felt no ownership. The people knew someone would come and fix them, and sure enough, some NGO came along and fixed them after a year or two.

I can’t think of a clearer way to discourage people from investing in their own town than by making them feel it’s unnecessary.

This is obviously an anecdote, but it exemplifies the patterns I saw throughout Mali. My village had four concrete buildings, and all of them had been built by NGOs. My neighbors were wonderful people, and wonderful partners. They welcomed the cash I raised to build a solar electricity system in the little health clinic, but when it broke they didn’t raise money or effort to fix it.

I am far from the first person offering this analysis. William Easterly and Dambisa Moyo are two economists who arge that aid is antithetical to development for a variety of reasons: disincentivizing ownership, crowding out local investment and pushing up value of local currency.

Dr. Moyo goes a step further than other aid critics: she asserts

that the aid is bad for Africa. I think she’s right; my experience is the anecdotal reinforcement of her research. So what’s the solution? I don’t know. But I do know aid is not working for Mali.

I plan to write more about alternatives to traditional aid; there are some case studies to come.

http://www.teachamantofish.org.uk/ I think there is something very human about wanting to do for yourself. When others do for you it takes away incentive and in a way shames. Even a very young child will watch a demonstration (just long enough to “get it”) and then quickly grab the toy away and do it by themself. It takes a lot of patience to teach how to do something. It’s so much easier to do it. I think Westerners are very impatient and we would rather get it done and move on instead of teaching the lesson in a slow, painstaking way.

Pati, of course you are right. I think in our rush to “help” Africa, we end up perpetuating colonial relationships between the west and Africa. I was constantly reminded of this in Mali – I was there to “teach” health practices and forestry, but I didn’t know anything about living in Mali. I did have a lot to offer, but it’s pretty damn presumptuous of me to tell Malians how to manage their land when I don’t know the first thing about living in Mali.